Auckland • Christchurch • Dunedin • Gisborne • Hamilton • Invercargill • Napier-Hastings • Nelson • New Plymouth • Palmerston North • Rotorua • Tauranga • Wellington • Whanganui (Wanganui) • Whangarei

|

|

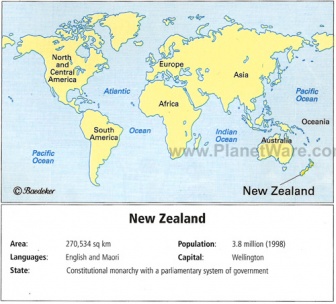

Location of New Zealand within the continent of Australia | |||

Map of New Zealand | |||

Flag Description of New Zealand: blue with the flag of the UK in the upper hoist-side quadrant with four red five-pointed stars edged in white centered in the outer half of the flag; the stars represent the Southern Cross constellation |

|||

|

Official name New Zealand (English); Aotearoa (Maori)

Form of government constitutional monarchy with one legislative house (House of Representatives [1211])

Head of state British Monarch: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General: Sir Jerry Mateparae

Head of government Prime Minister: John Key

Capital Wellington

Official languages English; Maori; New Zealand Sign Language2

Official religion none

Monetary unit New Zealand dollar (NZ$)

Population (2013 est.) 4,461,000COLLAPSE

Total area (sq mi) 104,515

Total area (sq km) 270,692

Urban-rural population

- Urban: (2011) 86.2%

- Rural: (2011) 13.8%

Life expectancy at birth

- Male: (2011) 79.3 years

- Female: (2011) 83 years

Literacy: percentage of population age 15 and over literate

- Male: not available

- Female: not available

GNI per capita (U.S.$) (2012) 30,620

1Statutory number is 120 seats; actual current number is 121 seats.

2Became official Aug. 10, 2006.

Background of New Zealand

The Polynesian Maori reached New Zealand in about A.D. 800. In 1840, their chieftains entered into a compact with Britain, the Treaty of Waitangi, in which they ceded sovereignty to Queen Victoria while retaining territorial rights. That same year, the British began the first organized colonial settlement. A series of land wars between 1843 and 1872 ended with the defeat of the native peoples. The British colony of New Zealand became an independent dominion in 1907 and supported the UK militarily in both world wars. New Zealand's full participation in a number of defense alliances lapsed by the 1980s. In recent years, the government has sought to address longstanding Maori grievances.

Geography of New Zealand

Demography of New Zealand

Government of New Zealand

Economy of New Zealand

- Economy - overview:

Over the past 20 years the government has transformed New Zealand from an agrarian economy dependent on concessionary British market access to a more industrialized, free market economy that can compete globally. This dynamic growth has boosted real incomes - but left behind some at the bottom of the ladder - and broadened and deepened the technological capabilities of the industrial sector. Per capita income rose for ten consecutive years until 2007 in purchasing power parity terms, but fell in 2008-09. Debt-driven consumer spending drove robust growth in the first half of the decade, helping fuel a large balance of payments deficit that posed a challenge for economic managers. Inflationary pressures caused the central bank to raise its key rate steadily from January 2004 until it was among the highest in the OECD in 2007-08; international capital inflows attracted to the high rates further strengthened the currency and housing market, however, aggravating the current account deficit. The economy fell into recession before the start of the global financial crisis and contracted for five consecutive quarters in 2008-09. In line with global peers, the central bank cut interest rates aggressively and the government developed fiscal stimulus measures. The economy pulled out of recession late in 2009, and achieved 2-3% per year growth in 2010-13. Nevertheless, key trade sectors remain vulnerable to weak external demand. The government plans to raise productivity growth and develop infrastructure, while reining in government spending.

- GDP (purchasing power parity):

- $136 billion (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 64

- $132.7 billion (2012 est.)

- $129.2 billion (2011 est.)

- note: data are in 2013 US dollars

- GDP (official exchange rate):

- $181.1 billion (2013 est.)

- GDP - real growth rate:

- 2.5% (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 130

- 2.7% (2012 est.)

- 1.4% (2011 est.)

- GDP - per capita (PPP):

- $30,400 (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 46

- $29,900 (2012 est.)

- $29,300 (2011 est.)

- note: data are in 2013 US dollars

- Gross national saving:

- 15.9% of GDP (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 104

- 14.5% of GDP (2012 est.)

- 14.5% of GDP (2011 est.)

- GDP - composition, by end use:

- household consumption: 58.1%

- government consumption: 19.9%

- investment in fixed capital: 20.2%

- investment in inventories: 0.5%

- exports of goods and services: 30%

- imports of goods and services: -28.7%

(2013 est.)

- GDP - composition, by sector of origin:

- agriculture: 5%

- industry: 25.5%

- services: 69.5% (2013 est.)

- Agriculture - products:

- dairy products, lamb and mutton; wheat, barley, potatoes, pulses, fruits, vegetables; wool, beef; fish

- Industries:

- food processing, wood and paper products, textiles, machinery, transportation equipment, banking, insurance, tourism, mining

- Industrial production growth rate:

- 1.9% (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 128

- Labor force:

- 2.413 million (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 113

- Labor force - by occupation:

- agriculture: 7%

- industry: 19%

- services: 74% (2006 est.)

- Unemployment rate:

- 6.4% (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 66

- 6.9% (2012 est.)

- Population below poverty line: NA%

- Household income or consumption by percentage share:

- lowest 10%: NA%

- highest 10%: NA%

- Distribution of family income - Gini index: 36.2 (1997)

- country comparison to the world: 86

- Budget:

- revenues: $69.17 billion

- expenditures: $72.65 billion (2013 est.)

- Taxes and other revenues:

- 38.2% of GDP (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 51

- Budget surplus (+) or deficit (-):

- -1.9% of GDP (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 86

- Public debt:

- 38.4% of GDP (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 98

- 38.1% of GDP (2012 est.)

- Fiscal year:

- 1 April - 31 March

- note: this is the fiscal year for tax purposes

- Inflation rate (consumer prices):

- 1.3% (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 37

- 1.1% (2012 est.)

- Central bank discount rate:

- 2.5% (31 December 2009)

- country comparison to the world: 70

- 5% (31 December 2008)

- Commercial bank prime lending rate:

- 5.7% (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 135

- 5.82% (31 December 2012 est.)

- Stock of narrow money:

- $30.03 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 60

$29.87 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Stock of broad money:

- $91.28 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 56

- $84.55 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Stock of domestic credit:

- $256.3 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 37

- $265.6 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Market value of publicly traded shares:

- $NA (31 December 2012 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 41

- $71.66 billion (31 December 2011)

- $71.83 billion (31 December 2010 est.)

- Current account balance:

- -$8.358 billion (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 173

- -$8.508 billion (2012 est.)

- Exports:

- $37.84 billion (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 62

- $37.87 billion (2012 est.)

- Exports - commodities: dairy products, meat, wood and wood products, fish, machinery

- Exports - partners: Australia 21.1%, China 15%, US 9.2%, Japan 7% (2012)

- Imports: $37.35 billion (2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 63

- $37.04 billion (2012 est.)

- Imports - commodities: machinery and equipment, vehicles, aircraft, petroleum, electronics, textiles, plastics

- Imports - partners: China 16.4%, Australia 15.2%, US 9.3%, Japan 6.5%, Singapore 4.8%, Germany 4.4% (2012)

- Reserves of foreign exchange and gold:

- $20.01 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 60

- $17.58 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Debt - external:

- $81.36 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 52

- $85.18 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Stock of direct foreign investment - at home:

- $84.2 billion (31 December 2013 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 46

- $81.36 billion (31 December 2012 est.)

- Stock of direct foreign investment - abroad:

- $59.08 billion (31 December 2009)

- country comparison to the world: 37

- Exchange rates:

- New Zealand dollars (NZD) per US dollar -

- 1.247 (2013 est.)

- 1.2334 (2012 est.)

- 1.3874 (2010 est.)

- 1.6002 (2009)

- 1.4151 (2008)

More on Economy of New Zealand

New Zealand’s economy is developed, but it is comparatively small in the global marketplace. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, New Zealand’s standard of living, based on the export of agricultural products, was one of the highest in the world, but after the mid-20th century the rate of growth tended to be one of the slowest among the developed countries. Impediments to economic expansion have been the slow growth of the economy of the United Kingdom (which formerly was the main destination of New Zealand’s exports) and its eventual membership in the European Community (later the European Union) and the high tariffs imposed by the major industrial nations against the country’s agricultural products (e.g., butter and meat).--->>>>>Read More<<<<

Energy of New Zealand

Communication of New Zealand

- Telephones - main lines in use:

- 1.88 million (2012)

- country comparison to the world: 61

- Telephones - mobile cellular:

- 4.922 million (2012)

- country comparison to the world: 113

- Telephone system:

- general assessment: excellent domestic and international systems

- domestic: combined fixed-line and mobile-cellular telephone subscribership exceeds 150 per 100 persons

- international: country code - 64; the Southern Cross submarine cable system provides links to Australia, Fiji, and the US; satellite earth stations - 8 (1 Inmarsat - Pacific Ocean, 7 other) (2011)

- Broadcast media:

state-owned Television New Zealand operates multiple TV networks and state-owned Radio New Zealand operates 3 radio networks and an external shortwave radio service to the South Pacific region; a small number of national commercial TV and radio stations and many regional commercial television and radio stations are available; cable and satellite TV systems are available (2008)

- Internet country code:

- .nz

- Internet hosts:

- 3.026 million (2012)

- country comparison to the world: 34

- Internet users:

- 3.4 million (2009)

- country comparison to the world: 62

Transportation of New Zealand

- Airports: 123 (2013)

- country comparison to the world: 48

- Airports - with paved runways:

- total: 39

- over 3,047 m: 2

- 2,438 to 3,047 m: 1

- 1,524 to 2,437 m: 12

- 914 to 1,523 m: 23

- under 914 m: 1 (2013)

- Airports - with unpaved runways:

- total: 84

- 1,524 to 2,437 m: 3

- 914 to 1,523 m: 33

- under 914 m:

- 48 (2013)

- Pipelines: condensate 331 km; gas 1,936 km; liquid petroleum gas 172 km; oil 288 km; refined products 198 km (2013)

- Railways:

- total: 4,128 km

- country comparison to the world: 42

- narrow gauge: 4,128 km 1.067-m gauge (506 km electrified) (2008)

Roadways:

- total: 94,160 km

- country comparison to the world: 50

- paved: 62,759 km (includes 199 km of expressways)

- unpaved: 32,143 km (2012)

- Merchant marine:

- total: 15

- country comparison to the world: 101

- by type: bulk carrier 3, cargo 3, chemical tanker 1, container 1, passenger/cargo 5, petroleum tanker 2

- foreign-owned: 7 (Germany 2, Hong Kong 1, South Africa 1, Switzerland 2, UK 1)

- registered in other countries: 5 (Antigua and Barbuda 2, Cook Islands 2, Samoa 1) (2010)

- Ports and terminals:

- major seaport(s): Auckland, Lyttelton, Manukau Harbor, Marsden Point, Tauranga, Wellington

Millitary of New Zealand

- Military branches:

- New Zealand Defense Force (NZDF): New Zealand Army; Royal New Zealand Navy; Royal New Zealand Air Force (Te Hokowhitu o Kahurangi, RNZAF) (2013)

- Military service age and obligation:

17 years of age for voluntary military service; soldiers cannot be deployed until the age of 18; no conscription; 3 years of secondary education required; must be a citizen of NZ, the UK, Australia, Canada, or the US, and resident of NZ for the previous 5 years (2013)

- Manpower available for military service:

- males age 16-49: 1,019,798

- females age 16-49: 1,003,429 (2010 est.)

- Manpower fit for military service:

- males age 16-49: 843,526

- females age 16-49: 828,779 (2010 est.)

- Manpower reaching militarily significant age annually:

- male: 30,846

- female: 28,825 (2010 est.)

- Military expenditures: 1.13% of GDP (2012)

- country comparison to the world: 89

- 1.12% of GDP (2011)

- 1.13% of GDP (2010)

Transnational Issues of New Zealand

- Disputes - international:

- asserts a territorial claim in Antarctica (Ross Dependency)

- Illicit drugs:

- significant consumer of amphetamines

Instituting Social Welfare of New Zealand

From the outset, the country has been in the forefront of social welfare legislation. New Zealand was the world's first country to give women the right to vote (1893). It adopted old-age pensions (1898); a national child welfare program (1907); social security for the elderly, widows, and orphans, along with family benefit payments; minimum wages; a 40-hour workweek and unemployment and health insurance (1938); and socialized medicine (1941).

New Zealand fought with the Allies in both world wars as well as in Korea. In 1999, it became part of the UN peacekeeping force sent to East Timor.

In recent years, New Zealand has introduced extremely liberal social policies. In June 2003, Parliament legalized prostitution and in Dec. 2004, same-sex unions were recognized. In 2005, Helen Clark was elected for the second time. She lost her reelection bid in 2008, when the center-right National Party, led by John Key, took 45.5% of the vote in parliamentary elections. Clark's Labour Party garnered 33.8%. Key became prime minister in November. Key's win ended nine years of governance by the Labour Party.

New Zealand Legalizes Same-Sex Marriage

On April 17, 2013, New Zealand's Parliament voted 77 to 44 in favor of same-sex marriage. Prime Minister John Key supported the legislation. The passing of the law made New Zealand the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to legalize same-sex marriage.

The new marriage equality law, which goes into effect in August 2013, also allows same-sex couples to adopt children. Their marriages are also recognized in other countries. With the passing of the legislation, New Zealand becomes the 13th country in the world where same-sex marriage is legal.

Culture Life of New Zealand

- Cultural milieu

New Zealand’s cultural influences are predominantly European and Maori. Immigrant groups have generally tended to assimilate into the European lifestyle, although traditional customs are still followed by many Tongans, Samoans, and other Pacific peoples. Maori culture suffered greatly in the years of colonization and into the 20th century, and many Maori were torn between the pressure to assimilate and the desire to preserve their own culture. However, since the 1950s there has been a cultural renaissance, with a determined effort to preserve and revive artistic and social traditions. The culture of the pakeha (the Maori term for those of European descent) has come to incorporate many aspects of Maori culture. The biennial Te Matatini festival, first held in 1972, celebrates Maori culture, especially the traditional dance and song performances known as kapa haka. The festival is held over several days, each time in a different region of New Zealand, and culminates in the national kapa haka championship.--->>>>Read More.<<<

History of New Zealand

Maoris were the first inhabitants of New Zealand, arriving on the islands in about 1000. Maori oral history maintains that the Maoris came to the island in seven canoes from other parts of Polynesia. In 1642, New Zealand was explored by Abel Tasman, a Dutch navigator. British captain James Cook made three voyages to the islands, beginning in 1769. Britain formally annexed the islands in 1840.

The Treaty of Waitangi (Feb. 6, 1840) between the British and several Maori tribes promised to protect Maori land if the Maoris recognized British rule. Encroachment by British settlers was relentless, however, and skirmishes between the two groups intensified.

Literature of New Zealand

Maori narrative: the oral tradition

Like all Polynesian peoples, the Maori, who began to occupy the islands now called New Zealand about 1,000 years ago, composed, memorized, and performed laments, love poems, war chants, and prayers. They also developed a mythology to explain and record their own past and the legends of their gods and tribal heroes. As settlement developed through the 19th century, Europeans collected many of these poems and stories and copied them in the Maori language. The most picturesque myths and legends, translated into English and published in collections with titles like Maori Fairy Tales (1908; by Johannes Carl Andersen), were read to, or by, Pakeha (European) children, so that some—such as the legend of the lovers Hinemoa and Tutanekai or the exploits of the man-god Maui, who fished up the North Island from the sea and tamed the sun—became widely known among the population at large.

Oratory on the marae (tribal meeting place), involving voice, facial expression, and gesture, was, and continues to be, an important part of Maori culture; it is difficult to make a clear distinction, such as exists in written literatures, between text and performance. Nor was authorship always attributable. And the Maori sense of time was such that legend did not take the hearer back into the past but rather brought the past forward into the present, making the events described contemporary.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, the Maori people, disastrously affected by European “minor” diseases to which they had only weak resistance, appeared to be in decline, and European scholars recorded as much Maori legend as they could, believing that the Maori would die out and that their oral culture, highly figurative and often of rare poetic beauty, deserved preservation. Some of this material was published; a great deal more was stored in libraries and is studied today, not least by Maori students and scholars intent on recovering their own cultural past.

Although Maori individuals and groups have become notable performers of various kinds of European music, their traditional music also survives. To the 19th-century European ear, the words of Maori poetry were impressive and beautiful, but the music was “tuneless and monotonous” and tended to be ignored. It is, however, inseparable from the words, and the scholars Mervyn McLean and Margaret Orbell were the first to publish text and music together. McLean and Orbell distinguished three kinds of waiata (songs): waiata tangi (laments—for the dead, but also for other kinds of loss or misfortune), waiata aroha (songs about the nature of love—not only sexual love but also love of place or kin), and waiata whaiaaipo (songs of courtship or praise of the beloved). In addition, there are pao (gossip songs), poi (songs accompanying a dance performed with balls attached to flax strings, swung rhythmically), oriori (songs composed for young children of chiefly or warrior descent, to help them learn their heritage), and karanga (somewhere between song and chant, performed by women welcoming or farewelling visitors on the marae). Some chants are recited rather than sung. These include karakia (forms of incantation invoking a power to protect or to assist the chanter), paatere (chants by women in rebuttal of gossip or slander, asserting the performer’s high lineage and threatening her detractors), kaioraora (expressions of hatred and abuse of an enemy, promising terrible revenge), and the haka (a chant accompanied by rhythmic movements, stamping, and fierce gestures, the most famous of these being war dances that incorporate stylized violence). In every aspect of this tradition, the texts, which in pre-European times survived through memorization, were inseparable from gestures and sometimes music. The most widely used modern development of these traditional forms is the waiata-a-ringa (action song), which fits graceful movements to popular European melodies.

Modern Maori literature

Until the 1970s there was almost no connection between the classical Maori tradition, preserved largely as a historical record, and the development of a postcolonial English-language literature of New Zealand. When Maori writers began to appear after World War II, they wrote in English, and the most notable of them knew little or nothing of the Maori language. In 1966 Jacqueline Sturm, wife of the poet James K. Baxter, became the first Maori writer to appear in a major anthology of New Zealand short stories. By that time, Hone Tuwhare, the first Maori poet to make a strong impression in English, had published his first book, No Ordinary Sun (1964). Witi Ihimaera’s short stories, collected in Pounamu, Pounamu (1972; “Greenstone, Greenstone”), and his novel Tangi (1973) seemed finally to establish Maori writers as part of modern New Zealand writing. The Whale Rider (1987; film 2002) gained Ihimaera an international readership. Patricia Grace’s narratives of Maori life—Mutuwhenua: The Moon Sleeps (1978), The Dream Sleepers, and Other Stories (1980), Potiki (1986)—were very widely read, especially in schools as part of a broad effort in New Zealand to encourage the study of Maori writing. And Keri Hulme’s The Bone People (1983), winner of Britain’s Booker Prize in 1985, probably outsold, both at home and abroad, any other book written during the postwar period. In the work of these writers, the language is English, the forms (particularly in fiction) are European, and “Maoriness” is partly a matter of subject, partly of sensibility, and partly (as in the case of Hulme, who has only one Maori great-grandparent and who changed her given name from Kerry to Keri) sympathetic identification.

But, increasingly through the 1980s, there was a tendency to politicize Maori issues in literature, something seen clearly in Ihimaera’s The Matriarch (1986) and in some of the later fictions of Grace, where the misfortunes of the Maori are laid, sometimes angrily, at the Pakeha door. A reaction against this came from Maori novelist Alan Duff—author of Once Were Warriors (1990; film 1994)—who argued that the Maori must take responsibility for their own failures and find the means to correct them and who spoke somewhat scornfully of his fellow Maori writers, saying that they sentimentalize Maori life. This polarization within the Maori literary community continued with the publication of Grace’s Cousins (1992) and Ihimaera’s Bulibasha (1994) on the one hand, both of which present positive images of a people who were damaged by colonialism and racism but who are fighting back, and with Duff’s What Becomes of the Broken Hearted? (1996) on the other hand, in which salvation for the Maori is again seen as lying within integration, education, and acceptance of individual responsibility. Duff’s controversial view was taken further in his autobiographical Out of the Mist and Steam (1999), in which his abusive Maori mother seems intended to be seen as typical while his bookish, intellectual Pakeha father represents a path of escape from the cycle of violence, failure, and despair. In the 1990s, after more than two decades of marriage and as the father of two daughters, Ihimaera publicly acknowledged his homosexuality; this added a further dimension not so much to his work itself but to the way it is read and the kind of interest taken in it.

A different form of politicization has come from Maori poets, some of whom rediscovered, partly through academic study, the classic forms of Maori poetry and returned to them in the Maori language. Since there are only a few thousand fluent speakers of the language (government statistics from 2001 said something over 10,000 adult Maori claimed to speak the language “well” or “very well”), this has been seen by some as an exercise in self-limitation, while to others it appears to be a brave assertion of identity; anthologies of New Zealand poetry now include examples of these new poets’ work in Maori with translations into English. Of the Maori poets writing in English, Robert Sullivan is the one whose work attracted the most attention at the turn of the 21st century.

Maori character and tradition have also found expression in the theatre, in plays written predominantly in English but with injections of Maori. Among the best of these works are Hone Kouka’s Nga tangata toa (published 1994; “The Warrior People”) and Waiora (published 1997; “Health”).

Pakeha (European) literature'

Modern discussions of New Zealand literature have not given much attention to the 19th century. Immigrant writers were Britishers abroad. Only those born in the “new” land could see it as New Zealanders; and even they, for most of the first 100 years of settlement (1820–1920), had to make conscious efforts to relocate the imagination and adapt the literary tradition to its new home. It is not surprising, then, that the most notable 19th-century writing is found not in poetry and fiction but rather in letters, journals, and factual accounts, such as Lady Mary Anne Barker’s Station Life in New Zealand (1870), Samuel Butler’s A First Year in Canterbury Settlement (1863), and, perhaps most notably, Frederick Maning’s Old New Zealand (1863).

The best of the 19th-century poets include Alfred Domett, whose Ranolf and Amohia (1872) was a brave if premature attempt to discover epic material in the new land; John Barr, a Scottish dialect poet in the tradition of Robert Burns; David McKee Wright, who echoed the Australian bush ballad tradition; and William Pember Reeves, born in New Zealand, who rose to be a government minister and then retired to Britain, where he wrote nostalgic poems in the voice of a colonist. They were competent versifiers and rhymers, interesting for what they record. But none of the poets stands out until the 20th century, the first being Blanche Edith Baughan (Reuben, and Other Poems [1903]), followed by R.A.K. Mason (In the Manner of Men [1923] and Collected Poems [1962]) and Mary Ursula Bethell (From a Garden in the Antipodes [1929] and Collected Poems [1950]).

New Zealand literature, it might be said, was making a slow and seemly appearance, but already the whole historical process had been preempted by one brief life—that of Katherine Mansfield (born Kathleen Beauchamp), who died in 1923 at age 34, having laid the foundations for a reputation that has gone on to grow and influence the development of New Zealand literature ever since. Impatient at the limitations of colonial life, she relocated to London in 1908, published her first book of short stories (In a German Pension [1911]) at age 22, and, for the 12 years remaining to her, lived a life whose complicated threads have, since her death, seen her reappearing in the biographies, letters, and journals of writers as famous as T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Bertrand Russell, and D.H. Lawrence. More important, she “altered for good and all” (in the words of the British writer Elizabeth Bowen) “our idea of what goes to make a story.” Two additional books published in her lifetime (Bliss and Other Stories [1920] and The Garden Party, and Other Stories [1922]) were followed by posthumously published stories, collections of poems, literary criticism, letters, and journals. She became for a time a major figure, faded for two decades, and was rediscovered in the 1970s by feminists and by scholars examining the Bloomsbury group. It seemed, from any perspective, that Mansfield remained a New Zealand writer whose best work was that in which she had re-created the country and family she had grown up in.

Mansfield once wrote, “I want to make my own country leap in the eyes of the Old World”—and she did it. She also made the short story respectable, established it as a form sufficient in itself for a writer’s reputation to rest on, and made it a staple of New Zealand writing. But she never completed a novel.

The first important New Zealand novels came from two writers whose scene was northern New Zealand: William Satchell (The Land of the Lost [1902], The Toll of the Bush [1905], and The Greenstone Door [1914]) and Jane Mander (The Story of a New Zealand River [1920]). They were followed by John A. Lee, whose Children of the Poor (1934), mixing fiction and oratory, was drawn from his own experience of childhood poverty in the South Island; Robin Hyde, who in The Godwits Fly (1938) still wrestled with the sense of colonial isolation; and John Mulgan, whose Man Alone (1939) held in balance both the colonial romanticism of the solitary figure in the empty landscape and the leftist romanticism of “men moving together” to change the world. In the 1930s Ngaio Marsh began publishing the detective novels for which she became internationally known.

New Zealand in 2011

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2011 est.): 4,407,000 Capital: Wellington Head of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governors-General Sir Anand Satyanand, Dame--->[[New Zealand in 2011|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2010

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2010 est.): 4,369,000 Capital: Wellington Head of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Sir Anand Satyanand Head--->[[New Zealand in 2010|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2009

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2009 est.): 4,317,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Sir Anand Satyanand Head--->[[New Zealand in 2009|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2008

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2008 est.): 4,268,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Anand Satyanand Head--->[[New Zealand in 2008|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2007

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2007 est.): 4,184,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Anand Satyanand Head--->[[New Zealand in 2007|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2006

New Zealand Area: 270,692 sq km (104,515 sq mi) Population (2006 est.): 4,141,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governors-General Dame Silvia Cartwright--->[[New Zealand in 2006|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2005

New Zealand Area: 270,534 sq km (104,454 sq mi) Population (2005 est.): 4,096,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Dame Silvia Cartwright Head--->[[New Zealand in 2005|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

New Zealand in 2004

New Zealand Area: 270,534 sq km (104,454 sq mi) Population (2004 est.): 4,060,000 Capital: Wellington Chief of state: Queen Elizabeth II, represented by Governor-General Dame Silvia Cartwright Head--->[[New Zealand in 2004|>>>>Read On.<<<<]

TOP 10 FACTS ABOUT NEW ZEALAND

Disclaimer

This is not the official site of this country. Most of the information in this site were taken from the U.S. Department of State, The Central Intelligence Agency, The United Nations, [1],[2], [3], [4], [5],[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14],[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24],[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30],[31], [32], [33], [34], and the [35].

Other sources of information will be mentioned as they are posted.