75th Cagayan Liberation Feature: Life During Wartime

Life During Wartime

When Cagayan de Oro had to mark the 75th Anniversary of its Liberation from Imperial Japan on May 12, 2020 behind closed doors, it recalled a similar situation when everyone’s freedom of movement was drastically curtailed by the Japanese Occupation from 1942 to 1945.

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) imposed tight restrictions on travel between towns and travelers had to provide “passes” similar to the Barangay Exit Pass permits only one person to step outside a residence for essential errands like medicines, foods and the like.

In fact, those violating existing community protocols and loudly complaining in social media about having their freedom of movement constrained should consider themselves lucky they only get a pat on the wrist or at worst, a fine to contend with. During the Japanese occupation, violators often found themselves imprisoned, or worse, tortured and killed for merely being suspected guerrillas or spies.

However, what most people could relate to during these times of the global pandemic is the adverse effects on their livelihood, household incomes and as a consequence, their daily bread, that in hindsight, is minuscule compared to the deprivations, fear and stress our lolas and lolos experienced during the three long years of the Japanese occupation.

3 Taong Walang Diyos

When the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro came out last April to encourage the establishment of household and community gardening for local food production to help sustain especially vulnerable residents in the informal sector, the unemployed, and those unable to be gainfully employed at this time, it was a virtual throwback to those “3 Taong Walang Diyos” as how the title of a popular local movie then describes the dark days of the Second World War.

Since many farms were abandoned and many farmers hiding out in the hills to escape the Japanese and local bandits, the shortage of food was a daily problem that haves and have-nots alike had to deal with.

Agriculture Top Priority

By sheer necessity, agriculture needed to be given priority.

In Misamis Oriental and almost all provinces occupied by the guerrillas, Army Communal Farms were under cultivation. These were cultivated by civilians under the so-called “pagina system”.

All the produce was for the Army. Evacuees were permitted to cultivate abandoned parcels of land and to them went the produce. Short season crops were produced intensively.

Community farms and victory gardens, poultry and hog raising projects, sponsored by the Army and civil officials, were intensified everywhere.

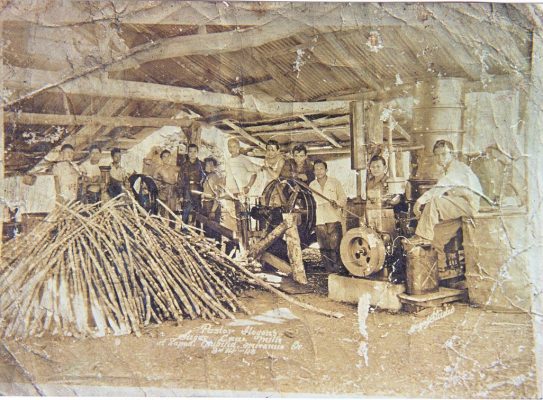

As vividly described by the late Cpl. Jesus B. Ilogon in his “Memoirs of a Guerrilla: The Barefoot Army”, his father Pastor P. Ilogon, Sr., as the Chief Food Administrator for the 109th Infantry Regiment, frequently and generously shared the produce of his farm in Lapad, Alubijid (now Laguindingan) with soldiers and civilians alike.

“Every space of the land was cultivated. Papa (Pastor Ilogon, Sr.) planted seven hectares of sugar cane, then constructed a crapetche(sugar mill) powered by huge carabaos. He planted five hectares of cassava (camoteng kahoy), and the rest with peanuts, corn, camote, and bananas (kantong and kadisnon). His five hectares in nearby poblacion Laguindingan was fully planted with corn by tenant Isias Madjos. Because of water irrigation, the four hectare ricefield in nearby Tanabog, Alubijid was planted twice a year by tenant Amado Llamera.”

“His rice produced in Bohol was transported by Barcos Dos Velas (known in local parlance as plain Dos Velas).” “From Alubijid, they were carried to Lapad by a train of carabaos. We had the luxury of eating rice as our staple food. He raised more than 100 white leghorns (chickens). The chickens were healthy because they were fed with aroma (ipil-ipil) seeds and leaves. Aroma trees grew in abundance in the farm.”

Manticao, Initao, Misamis Oriental was the corn granary of both the 109th and 120th Regiments. Alubijid, Misamis Oriental, El Salvador, Cagayan and Libertad, Initao were the salt and crude soap producing areas. Soap was made from coconut oil and wood ashes. Gitagum, Alubijid was a safe haven of big Dos Velas carrying tons of goods from Negros, Cebu, Bohol, and Misamis Occidental.

But as the war entered its third year in 1944, food became scarcer and corn increasingly difficult to obtain. Despite this, Ilogon described the prevailing situation at their farm in Lapad:

“The fields were a beehive of activity with peanuts, camote and bananas being harvested and processed. For three years, the farm was constantly occupied with the cycle of planting, harvesting, storing and selling.”

“Some evacuees survived by bartering their clothes for food. Others subsisted on boiled unripe bananas and the bananas inner core. Evacuees from afar camped on the cassava plantation and made cassava chips from the roots, still others shucked. then shelled the kernels off corn cobs to store them in sacks. Traders coming from as far as Imbatog and Talakag, Bukidnon, slept in the field and were up before dawn to load their cattle with sacks of matamis (brown sugar).”

However, in spite of favorable weather during the period February 1943-November 1944, food shortages occurred due to heavy floods in free Cagayan which cost the lives of 47 persons and the loss of approximately 200-300 cavans of rice and corn in 1943. Locust infestation in June 1943 in Free Cagayan and the municipal districts of Lumbia, destroyed approximately 60% of standing crops.

In Bukidnon before the war, the cattle industry was flourishing, but this was virtually wiped out. People, like the other provinces, resorted to agriculture by cultivating forested areas.

Despite the confluence of plant pests and animal diseases, floods and drought, and on top of it active Japanese patrols which seemed to have conspired together during a period of turmoil and distress, the products produced improved the food situation impressively and led to the lowering of prices.

Carabao sleds, carts and sailboats and launches were some of the means utilized in the transportation of foodstuffs from one place to another. In two of three sectors, trucks were used but only for short distances as most of the roads and bridges were unserviceable –either blasted purposely in the early days of the war or destroyed by action of the elements, and never repaired.

Home & Village-Level Industries

In all places, the civil government waged a campaign directly supported by the Army for the development of home industries. More Industries Encouraged (pp. 128)

Weaving was encouraged. Cloth was manufactured from cotton, ramie and abaca fiber. Finished products were in great demand, which, of course, could not be met because of the limited production. Cigarettes, crudely manufactured, substituted for American brands- though a poor substitute, were in great demand. The biggest handicap was lack of rolling paper.

Salt, soap, coconut oil, and alcohol from tuba were produced in sufficient quantities to supply civilian and army needs. The intensified stimulus for the production of food products included the tending of home gardens, and the employment of unarmed soldiers in Army farm projects.

In the provinces of Agusan, Surigao, Misamis Oriental , Misamis Occidental and Zamboanga, merchants frequented the market place to sell their good and commodities. Business was retail. Articles sold were rice, corn, soap, salt, fish, sugar, vegetables and other foods.

Inter-island trade

It is consoling to note that even during the dark days, Mindanao had been able to share food with adjacent areas in the Visayas, like Leyte, Cebu and Bohol. Slow-moving bancas were used to ply between Agusan and the Visayas. Productive industries consisted in the manufacture of tuba, nipa wine and nipa shingles. Weaving was lucrative.

In Lanao, periodic trips were undertaken by traders from Bohol, Negros, Siquijor, Cebu and Camiguin, bringing in sugar, garments, dried and salted fish, medicines and others. On their return trip, they brought with them rice, corn, and other food which were lacking in their places. Very often, these trips were undertaken by the ubiquitous Dos Velas sailboats.

“Barco Dos Velas was a 2-masted sail boat common between Visayas and Mindanao during colonial times,” said Antonio J. Montalvan II, a Europe-based Filipino public writer, social anthropologist, university professor and heritage activist. “Vela means candle in Spanish and it was called such since its two masts looked like two upright candles. These were the sailboats which many Visayan immigrants took when they moved to Mindanao.”

The sailboats and bancas revived the inter-island trade interrupted by the war. They traded in salt, corn, rice, guinamos, dried fish,, sugar and soap.

Normal trade relations existed between Lanao and Misamis Occidental. This trade relation, however, between these two provinces and from other islands in the Visayas, were at times paralyzed due to active Japanese patrols, both by land and sea.

The daring viajeros crossed the sea at night and hid in island coves during daytime to avoid Japanese sea patrols that prowled Macajalar and Iligan Bays searching for guerrillas going to and fro Fertig’s headquarters at Misamis, Misamis Occidental.

It was the usual practice of guerrillas going to Misamis to commandeer a sailboat, cross Iligan Bay at night to avoid Japanese motor launches based in Iligan, and arrive in Jimenez in the morning.

When a banca was commandeered, its skipper was given a “Jefe de Viaje”(Safe Passage Pass) by the area guerrilla commander which guaranteed him safe passage through territories controlled by the guerrillas. However, savvy traders were also known to obtain similar safe passage passes from the Japanese (written in Nihongo) which they flashed when hailed by Japanese patrols. Of course, these were usually kept under wraps from the guerrillas.

The Japanese often intercepted the sailboats at sea, confiscating their cargo, and took the crew prisoner. Because of this, business declined and later, markets and retail stores were closed. The sudden rise of commodity prices inevitably followed.

Unlike the other provinces, Cotabato and Davao whose coastal areas were occupied by the Japanese, and land-locked Bukidnon, could not fully sustain inter-island commerce. Salt and fish, for instance, were difficult to obtain. Native cloth like pinocpos and saguran made from buri palm, were brought in by some bancas from other provinces, were also difficult to secure. Some inhabitants who depended on selling the rice, corn or tobacco they cultivated, also found it hard to trade due to Japanese patrols which confiscated their produce.

So the next time you hear someone griping about how the coronavirus have made life so much harder, remind him our grandparents fared even worse during the “3 Taon Walang Diyos” and survived to tell their tales.

With all the help people are now receiving from their barangays, local government units and national agencies like DOLE, DSWD, DTI and DA, not to mention the hundreds of good Samaritans and NGOs sharing their blessings, they should stop complaining and stay put at home.

The better we comply with the health protocols of social distancing, mandatory face masks, and limiting time outside our residences to essentials, our chances of beating this virus increases and with it, our chances or returning to closer semblance of how it was before. (Compiled by Mike Baños)

Recent Posts

Islam as a Political System Wrapped in Religion

1. The Humble Beginnings: A Man of Ambition Born into a poor family in Mecca,…

America’s Missed Immigration Bonanza

America’s Missed Immigration Bonanza: Why Vetting and Expansion Are the Future With border security…

Acting out, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Atik atik

Acting out in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Atikatik Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for…

Typewriter, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Makinilya

Typewriter in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Makinilya Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for "Makinilya"…

Merciful, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Misericordioso

Merciful in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Misericordioso Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for "Misericordioso"…

Compliment, in Chavacano or chabacano is: Complimento

Compliment in Chavacano or Chabacano is: Complimento Alternate chavacano word: Alternate English word for "Complimento"…